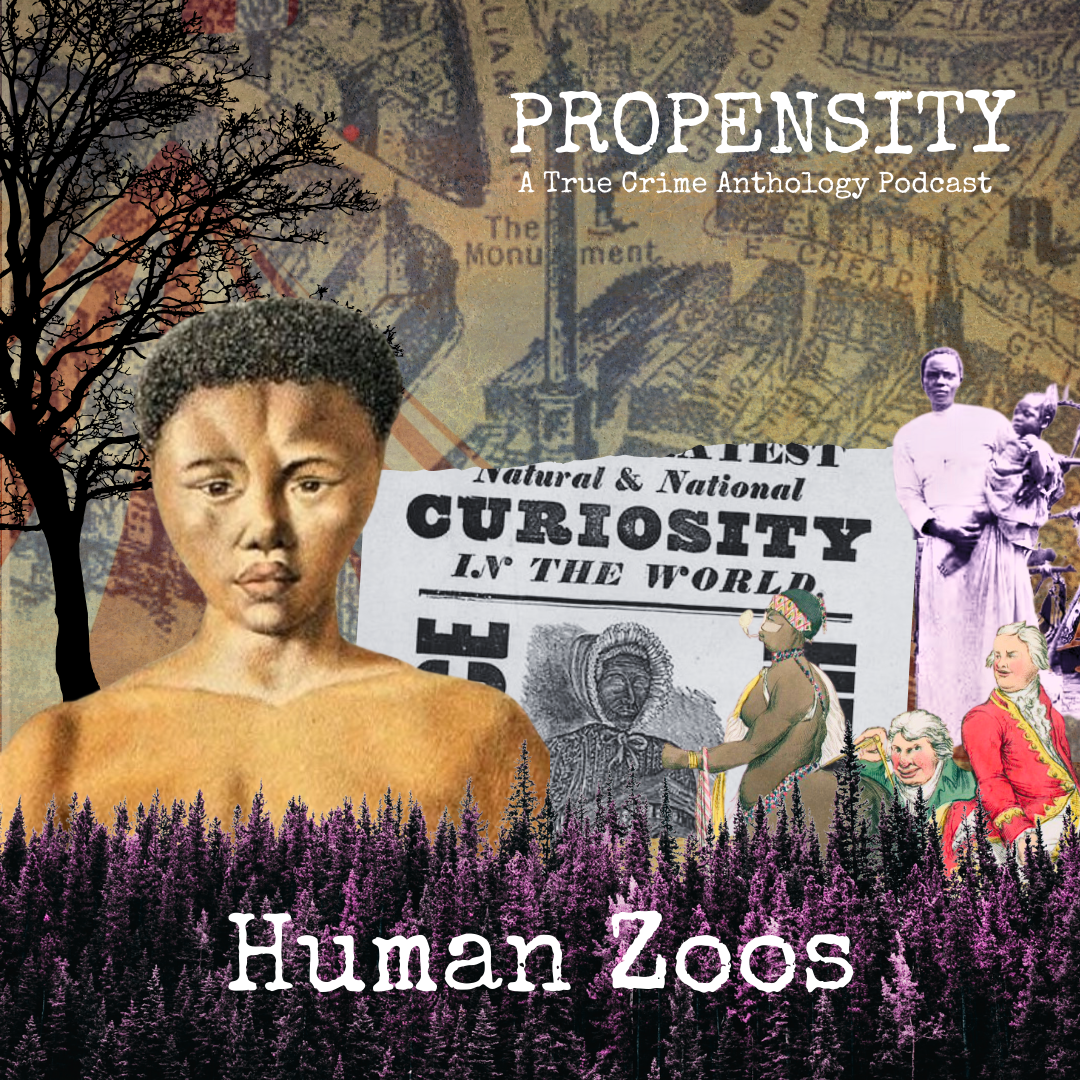

Episode 6: Exhibit A - Colonial Legacies, Eugenics & Human Zoos: Sarah Baartman

Listen to episode here:

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, captive individuals were bought, sold, and displayed as spectacle for paying audiences in human zoos. Sometimes individuals with physical deformities and abnormal appearances were sold by their families to freak shows. Sometimes they had no choice but to sell their services and bodies to untrustworthy and exploitative promoters to avoid becoming destitute. Often, there was a racial component to those being displayed – the more unusual and exotic the individual, the more money that could be made by unscrupulous exhibitors.

History of Colonialism & Scientific Racism:

We can’t discuss human zoos without first looking at the conditions that allowed them to not only exist, but to flourish in the United States and Europe. The very concept of exhibiting human beings to paying audiences is one that is steeped in colonialism, eugenics, and scientific racism. Author Jurgen Osterhammel describes colonialism as being ‘a relationship between an indigenous (or forcibly imported) majority and minority of foreign invaders’. We can apply colonialism to refer to any country or civilisation that has attempted to forcibly subjugate another population.

The concept of eugenics predates the actual term eugenics. In 400 BC, Plato suggested applying selective breeding to humans, so that supposed ‘high-quality’ individuals could be paired together to encourage the physical and mental traits favoured by that society. A form of eugenics was also practiced in ancient Sparta, where infanticide was common, and any child who had an obvious physical deformity was immediately killed.

Joice Heth:

In America, human zoos and freak shows were a regular form of entertainment. P.T. Barnum was a showman, promotor and circus owner who regularly displayed people all over North America and Europe. He also perpetrated multiple hoaxes and created fantastical stories about the people in his exhibits. One of the earliest hoaxes that Barnum was responsible for, was the exploitation of Joice Heth, whom he claimed was the 161-year-old former wet-nurse of George Washington.

Joice Heth’s birth year is unknown. It is estimated that she was born circa 1756, and almost definitely into slavery. Joice was a black American slave. We can speculate that she had a husband and children and even grandchildren and great-grandchildren, but none of these facts about her life are on record.

Joice’s written records begin in 1835, when she was purchased by a man called John S. Bowling and exhibited in Kentucky. Later that same year, she was sold again to R.W. Lindsay and Coley Bartram, who falsely displayed Joice as having been the childhood nurse of George Washington. George Washington was born in 1732, meaning that his birth pre-dated Joice’s by 24 years, but this didn’t stop Lindsay and Bartram.

In 1835, Joice was 79 years old, frail, blind, and partially paralysed. Lindsay fabricated a narrative around Joice to extract the maximum value from the public, who would pay him to view her, but was unsuccessful in this endeavour, ultimately selling Joice to Barnam. P.T. Barnam refined the story of Joice’s background and printed posters containing the following text:

‘Joice Heth is unquestionably the most astonishing and interesting curiosity in the World! She was the slave of Augustine Washington, (the father of Gen. Washington) and was the first person who put clothes on the unconscious infant, who, in after days, led our heroic fathers on to glory, to victory, and freedom’.

On the 11th of August 1835, Barnam began to exhibit Joice at Niblo’s Garden, a theatre in Soho, Manhattan. For many who saw her, Joice’s appearance was proof enough that she was 161 years old, as claimed by those who displayed her. Others, including the press at the time, doubted Barnam’s claims. Joice died on the 19th of February 1836, just seven months after Barnum had first started to exhibit her.

Almost immediately after Joice’s death, Barnam announced that there would be a public autopsy. Dr David L. Rogers, a New York surgeon, was engaged to conduct the autopsy. Rogers began the autopsy before an audience of 1500 people. Rogers declared that Joice was not in fact 161 years old. To cover for his fraud, Barnam announced that the body being dissected was not actually Joice, and that she was alive and well and on tour in Europe. Later, Barnam admitted to the story being a hoax. By this time, Joice was dead, and he had extracted as much financial value from her in life, as well as in death, so he had nothing left to lose.

Sarah Baartman:

The most infamous tale of exploitation in human zoos is the story of Sarah Baartman. Sarah was a South African woman of Khoikhoi origins, born in the Camdeboo region of the Eastern Cape in 1789. The Dutch had established the first permanent colony in South Africa in Cape Town in 1652 and would remain a dominant force in the region for much of the next 350 years. By the time Sarah was an adult, the Dutch Cape Colony had become a British colony.

Sarah’s mother died while she was a young child, and her father was killed by Bushman. When she was 16 years old, she was married to a Khoekhoe man, and had reportedly had one child, who died in infancy. She spent her childhood and adolescent years working on Dutch European farms, as a servant. South African History Online state that Sarah’s husband was murdered by Dutch colonists in 1805.

Soon after this, she met a ‘free black’ trader called Pieter Willem Cezar. All source materials indicate that Sarah was born free, but in Colonial Africa, where people were viewed as commodities to be bought, sold, and exploited, this status was not to last. Sarah worked for the Cezar family in Cape Town for two years. First, as a washerwoman, and then as a nursemaid, working in Pieter’s household, and then for his brother Hendrik.

Sarah had an unusual body type by European standards. Reports suggest that she had steatopygia, which is a common condition found in Khoikhoi people, and others in the southern parts of the African continent. Steatopygia is characterised by excess levels of tissue accumulated primarily on the buttocks and thighs. This was enough to make Sarah a curiosity that could be used to make money by exhibiting her to European audiences, who viewed her as an exotic oddity.

Hendrik Cezar was an entrepreneur and always on the lookout for moneymaking schemes. In Sarah, he saw the potential to generate substantial profits. He began to show Sarah at the local city hospital in Cape Town in exchange for cash. Hendrik soon caught the attention of Scottish military surgeon Alexander Dunlop. Dunlop had a side business of providing British showmen with exotic animal specimens and believed that they could find success in exhibiting Sarah in Europe.

In 1810, Sarah, Hendrik and Dunlop left Cape Town to make the arduous journey to London. Before leaving for Europe, Hendrik had Sarah sign a contract, although Sarah was illiterate, so could not fully consent to the terms she was allegedly agreeing to. The contract made Sarah an indentured servant for an undisclosed number of years.

Dunlop secured accommodation for the group on Duke Street, St. James, which at the time was one of the most expensive areas in London. Two young African boys also lived with them, likely procured by Dunlop illegally during his time in Cape Town.

The British had abolished slavery three years earlier in 1807, but most slaves in British colonies were not actually freed until 1838. While the public marveled at Sarah’s exhibition, many people were morally opposed to displaying people for financial gain. In a BBC article, Justin Parkinson tells us that ‘campaigners were appalled at Baartman’s treatment in London’.

Exploitation:

The association of exaggerated genitalia and protruding fat deposits in the buttocks meant that Sarah was viewed as a sexual object by audiences and was often displayed almost entirely naked. She was allowed to wear a tan loincloth, upon her insistence that she cover up ‘what was culturally sacred’. It has been suggested that there was an element of ‘erotic projection’ by those who viewed Sarah, as she was perceived through the dual lenses of colonialism and patriarchy. Some of the promotional material at the time implied that Sarah was the ‘missing link between man and beast’.

Sarah soon caught the attention of abolitionists from the African Association who believed that she was being exploited by her handlers and was being held against her will. Leading abolitionist Zachary Macauley drove a newspaper campaign arguing for Sarah’s release. On the 24th of November 1810, just months after her arrival in Britain, the matter was taken to court. Sarah’s supporters contended that the men who had brought Sarah to London had referred to her as ‘property’ and that she was being exhibited under coercion and in degrading conditions. Sarah was questioned in court in Dutch for three hours, with an interpreter to relay her answers to the court in English. Dunlop was present in the courtroom for the duration of Sarah’s testimony. Many believe that this fact influenced her answers and furthered the claims of coercion.

Sarah’s testimony stated that she was not under restraint and had not been abused, and that she was entitled to half of the profits garnered from the shows. This directly contradicted the witness testimony of those who had witnessed her poor treatment and exploitation behind the scenes by both Hendrik and Dunlop. The case against Alexander Dunlop and Hendrik Cezar was dismissed due to lack of evidence.

Despite the earlier claims that Sarah was free to leave at any time and was completely independent in her decision to perform or not, it appears that she was ‘sold’ and changed hands several times. In September 1814, she travelled to France with a man called Henry Taylor, who subsequently sold her to an animal trainer called S. Réaux.

Voyeurism:

As mentioned previously, slavery was illegal in Britain, which afforded Sarah at least some rights and limited her mistreatment, at least legally. Slavery would not be abolished in France until April 1848. During her time in Paris, Sarah was essentially enslaved. She was exhibited at the Palais Royal in Paris, and later at private parties for the wealthy elite. The eugenics movement was taking off in France at the time, and Sarah became a specimen to be studied under what we now refer to as ‘scientific racism’.

The cruel treatment and relentless voyeurism Sarah endured after she arrived in France took its toll, and Sarah died on the 29th of December 1815, at the age of 26. Her cause of death was listed as ‘inflammatory and eruptive disease’. It has since been suggested that her death could have been a combination of alcoholism, pneumonia or even syphilis.

After her death, French anatomist, and naturalist Georges Cuvier, who had met Sarah while she was alive, conducted a dissection of her body, and took meticulous notes. Cuvier was a leading proponent of scientific racism. Prior to her dissection, Cuvier made a plaster cast of Sarah’s body. He also removed her brain and genitalia, pickling them in jars, and preserved her skeleton.

Another naturalist, Étienne Geoffrey Saint-Helaire applied on behalf of the Natural History Museum to have Sarah’s cast, skeleton and remaining organs displayed, as they were of scientific interest. His petition was approved, and her remains were displayed publicly in the Natural History Museum in Angers until 1974. We will return to Sarah’s story later in the episode.

Belgian Village:

In the late nineteenth century, King Leopold II of Belgium looked at the colonial expansion of other European countries in the African continent and decided that he wanted some of that action for himself. He unsuccessfully petitioned the Belgian government to support Belgian expansion to the Congo Basin, but those in power seemed to be ambivalent about this prospect.

This angered Leopold, who decided to proceed without governmental support to establish his own personal African colony. In 1885, Leopold had established the Congo Free State, but the people of that region were anything but free. A non-governmental organisation called the International African Association was set up to manage the Congo Free State. It had a single shareholder, King Leopold II, and operated as a corporate state.

1897 Congo Village:

The Belgian’s did not just view the Congolese as a form of labour, they also viewed them as an exotic curiosity that Europeans would pay to see exhibited. In 1897, King Leopold II imported approximately 267 native Congolese people to the Belgian capital, Brussels. It was Leopold’s intention to display the group in Tervuren, east of Brussels, where he had a colonial palace. He had built the Colonial Palace on the site of the former pavilion of the Prince of Orange that had been destroyed by a fire in 1879.

Leopold viewed the Colonial Palace and its displays, including his human zoo project, as propaganda to showcase his successes in the African colony. The Brussels International Exhibition took place between May to November 1897. As part of this display, three fenced replica Congolese villages were created. A fourth village operated by a Christian missionary, Abbot Van Impe was also established, but in contrast to the other villages, its purpose was to show the ’civilisation’ of native peoples through religion and education.

An estimated 1.3 million Belgians visited the Congolese exhibition, but the exploitative nature of the exhibit was not lost on some of the visitors. A journalist for La National wrote the following in an article published on the 10th of July 1897:

‘There is even something quite degrading for humanity, to see these unfortunate people parked like this, left to the sometimes distressing and degrading reflections of the white people who are rushing to the new show’.

The apparent financial success of the Congolese village exhibition meant that some form of public human exhibit was in place for many decades after the Brussels International Exhibition of 1897. By the later 1950s, the Belgian Congo were vying for independence. For Expo ‘58, the Belgian’s established the largest Congo village exhibition in history, far larger than the 1897 had been. This was in part to showcase their apparent successes in the Congo, and to justify their ongoing presence there to the public.

In total, 598 people were transported from the Congo to Belgium for the exhibit. Unlike the 1897 exhibition, the Congolese in 1958 were kept off-site and bussed in for the exhibition. They complained of cramped conditions and isolation, and by July 1958, many had left to return home. The Congolese exhibit closed soon after this, although the rest of Expo ’58 continued, as planned. This marked the final human zoo in modern history.

Sarah Baartman’s Legacy:

Sarah Baartman’s story was largely forgotten until 1981, when palaeontologist Stephen Jay Gould wrote about her story in his book The Mismeasure of Man. In 1994, when the African National Congress (ANC) came to power, newly elected President Nelson Mandela made a formal request to France to return Sarah’s remains to her homeland. On the 6th of March 2002, Sarah’s remains were finally returned to South Africa.

Sarah Baartman’s legacy exceeded her short life. In 2015, the Sarah Baartman District Municipality in the Eastern Cape province was named in her honour. An environmental protection vessel, the Sarah Baartman is named after her, along with a hall at the University of Cape Town. Sarah was not the first person stolen from her homeland or exploited for an audience who viewed her as nothing more than an object to be gawked at, but she is perhaps one of the most heavily discussed. The last human zoo exhibition was more than sixty years ago, but many former empires have yet to atone for their part in the wholescale dehumanisation and exploitation of millions of people.

Sources:

‘A Brief History of Dutch in Africa’, Europe Now.

https://www.europenowjournal.org/2018/02/28/a-brief-history-of-dutch-in-africa/

‘Anti-Irish sentiment’, Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anti-Irish_sentiment

‘Atrocities in the Congo Free State’, Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atrocities_in_the_Congo_Free_State

‘Belgian Congo’, Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Belgian_Congo

Boffey, Daniel, ‘Belgium comes to terms with ‘human zoos’ of its colonial past’, The Guardian, 16th April 2018.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/apr/16/belgium-comes-to-terms-with-human-zoos-of-its-colonial-past

‘Colonialism’, Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colonialism

Crais, Clifton & Scully, Pamela, Sara Baartman and the Hottentot Venus: A Ghost Story and a Biography, Princeton Univeristy Press.

‘Cultural Imperialism’, Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultural_imperialism

Dreesbach, Anne, ‘Colonial Exhibitions, ‘Völkerschauen’ and the display of the ‘Other’’, European History Online, 3rd May 2012.

‘Eugenics’, History, 28th October 20179.

https://www.history.com/topics/european-history/eugenics

‘Eugenics’, Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eugenics

‘Eugenics and Scientific Racism’, National Human Genome Research Institute

https://www.genome.gov/about-genomics/fact-sheets/Eugenics-and-Scientific-Racism

‘George Washington’, Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Washington

Goodfellow, Sarah, ‘Hottentot Apron’, Encyclopedia.

https://www.encyclopedia.com/medicine/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/hottentot-apron

‘Hottentot (racial term)’, Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hottentot_(racial_term)

‘Human Zoo’, Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_zoo

‘Joice Heth’, Mount Vernon.

https://www.mountvernon.org/george-washington/facts/myths/joice-heth/

‘Joice Heth’, Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joice_Heth

Parkinson, Justin, ‘The significance of Sarah Baartman’, BBC, 7th January 2016.

https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-35240987

Pinoja, Letizia Gaja, ‘Dehumanisation, animalisation: inside the terrible world of Swiss human zoos’, The Conversation, 22nd June 2023.

‘Phrenology’, Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phrenology

‘P.T. Barnum’, Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/P._T._Barnum

Rutherford, Adam, ‘Where science meets fiction: the dark history of eugenics’, The Guardian, 19th June 2022.

https://www.theguardian.com/science/2022/jun/19/where-science-meets-fiction-the-dark-history-of-eugenics

‘Sarah Baartman’, Britannica.

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Sarah-Baartman

‘Sarah Baartman (1789-1815)’, Royal Collection Trust.

https://www.rct.uk/collection/661166/sarah-baartman-1789-1815

‘Sara ‘Saartje’ Baartman’, South African History Online.

https://www.sahistory.org.za/people/sara-saartjie-baartman

‘Sarah Baartman’, Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sarah_Baartman

Schofield, Hugh, ‘Human zoos: When real people were exhibits’, BBC, 27th December 2011.

https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-16295827

‘Steatopygia’, Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steatopygia

‘Terre Haute Hottentots’, Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Terre_Haute_Hottentots

‘The human zoo of Tervuren (1897), Africa Museum.

https://www.africamuseum.be/en/discover/history_articles/the_human_zoo_of_tervuren_1897

‘Thomas Hope (designer’, Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Hope_(designer)

‘1807 Abolition of the Slave Trade’, UK Parliament.